- Home

- John Grant

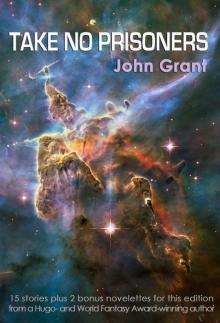

Take No Prisoners

Take No Prisoners Read online

Take No Prisoners

short fiction by

John Grant

Take No Prisoners

John Grant

In a universe that isn't ours, a hopelessly mismatched pair are thrown together in a potentially fatal encounter with incomprehensible technology left behind by an unknown transgalactic civilization. Back here on Earth, a hideous rape is even more hideously avenged by a child's dream. A middle-aged bourgeois husband recalls his life as drummer in a punk-rock group and the otherworldly strangeness of the singer he loved. A movie buff cannot explain why the offerings at his local fleapit seem to fly in the face of all reason. In a world comprising the residue left over after imagination has gone elsewhere, a Beast must embark on an endless quest to find his Beauty. And meanwhile there's another case to be solved outside time in the cozy-mystery village of Cadaver-in-the-Offing...

In the fifteen superbly literary stories of this, his first collection, Hugo- and World Fantasy Award-winning author John Grant goes to places other fantasy and SF writers have yet to find on the map.Take No Prisoners is a magnificent demonstration of why his imagination has been described as defying all genre categorization. As a special bonus, this new e-edition of Take No Prisoners includes two novelettes from the author's Leaving Fortusa cycle: "The Hard Stuff" and "Q"...

contents:

Wooden Horse

The Glad who Sang a Mermaid in from the Probability Sea

A Lean and Hungry Look

I Could Have a General Be / In the Bright King's Arr-umm-ee

Snare

The Dead Monkey Puzzle

All the Best Curses Last for a Lifetime

A Case of Four Fingers

Sheep

The Machine It Was That Cried

Coma

Mouse

How I Slept with the Queen of China

Imogen

MeTopia

bonus material:

The Hard Stuff

Q

Published by infinity plus at Smashwords

www.infinityplus.co.uk/books

Follow @ipebooks on Twitter

© John Grant 2004, 2010

Cover image © NASA, ESA, and M. Livio and the Hubble 20th Anniversary Team (STScI)

Smashwords Edition, Licence Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

The moral right of John Grant to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

eISBN: 9781458171337

Electronic Version by Baen Books

www.baen.com

DEDICATION

This is for Jane.

An offering from Dad.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Janis Ian for allowing me to quote her lyrics and for the enthusiasm she's expressed for this book; love to you both, Janis and Pat. My thanks to those who read the text and gave me permission to quote their comments: John Clute, Bob Eggleton, Jael, David Langford, Vera Nazarian and N. Lee Wood. Some of these stories were assisted by discussion over the years at the Milford (UK) Writers' Conference and at various Bl*ts; thanks to all who participated. My thanks, too, to the magazine and anthology editors who had the faith to publish these stories in the first place; Lou Anders was a particular encouragement at the late, lamented Bookface website. Bob Katz, my editor at Willowgate Press, first publisher of this book, was a delight throughout; a special thanks also to Lynn Katz. My daughter Jane read many of these stories when they were they were still fresh, raw and bleeding, and her advice helped me staunch a plethora of wounds. And my wife Pam puts up with me; I'd say she was an angel for doing so but they don't make angels that good.

—JG

And the writer said, "I wish you'd known me

when I still believed in the truth.

Now it's all I have left

along with my debts and lack of youth."

He said: "Take no prisoners.

Tell no lies.

No pretty songs of compromise.

Take no prisoners, tell no lies ..."

—Janis Ian, "Take No Prisoners"

Copyright © 1995 Rude Girl Publishing

Used by kind permission of Janis Ian

Wooden Horse

It was while I was studying for my doctorate in veterinary science that I first developed that passion for the cinema which came to dominate my later career, at the expense, alas, of all the dogs and cats and cows and horses I might have treated had my life gone according to the original plan. It's silly to wish one could change the past, of course, but sometimes I catch myself thinking that each of us should be given more than one life – not sequentially, but in parallel, so we could pursue several lifelines simultaneously. I would like to have been a vet as well as an expert on the movies, the author of over twenty critical studies, a reference work that I revise annually, and more articles and reviews than I could possibly have the time to count. But then the director calls for silence and I start speaking into the television camera, presenting some movie or another, or discussing the latest releases, and my fancy dies because I haven't the time to continue giving it life.

I wasn't born a movie fan. As I say, I was in my mid-twenties and studying for a doctorate when circumstances conspired to germinate an interest that I suppose, on reflection, must have been latent somewhere inside of me from the outset.

Those circumstances were not particularly glamorous. Mine isn't a tale of some mentor taking me under his wing and engendering in me a deep love of the silver screen. The main factors were: shortage of money; the rule that the laboratories and library were reserved exclusively for undergraduates on Monday afternoons; and the Rupolo Cinema on Broad Street.

They don't make movie theaters like the Rupolo any more. Nowadays, aside from the fringe cinemas you can find in the bigger cities that show either experimental movies of stupefying opacity or porn, or the latter masquerading as the former, just about all the movie theaters in the country are multi-screen links of this major chain or that one, all showing only the most blatantly commercial of the new releases. But in the days when I was a footloose postgraduate, forever counting my coins to make sure I could both eat and pay the rent, you could find little cinemas like the Rupolo in small towns all over America. Sure, they carried the new movies, but generally about three months behind – an interesting temporal dislocation because, by the time a movie came to a cinema near you, you tended to have forgotten all the television hype there'd been around the time of original release and, often enough, to be able to recall even the title only dimly. As well as these new/oldish movies, cinemas like the Rupolo took it upon themselves to show special items, to have matinees for the kids on a Saturday morning, to run occasional "seasons" devoted to one theme or another ... It was a golden era for public appreciation of the movies, thanks to those small and generally run-down cinemas, and we didn't fully realize it until it was – and they were – gone.

Whoever owned the Rupolo – and I never did discover who that was, or even think about it very much – had a penchant for old British war movies of the 1940s and 1950s, most of them in black-and-white and many of them originally intended to be support movies. (And that's an artfo

rm that likewise disappeared without our noticing: the B-movie.) He – I assume the owner was a he – was not totally devoid of commercial sense, mind you. He might have had a passion for these old movies, but he wasn't going to be fool enough to show them at any time when he might pull in a bigger paying audience for something new starring Robert Redford or Faye Dunaway. So the aged war movies were relegated to Monday afternoons, notoriously the leanest time of the week for movie theaters. Weekday afternoons are generally pretty quiet for the cinemas anyway, except during the school holidays; and Monday is the quietest of them all, as people recover from the excesses of the weekend.

But Monday afternoon was ideal for me. On my budget, I couldn't afford those weekend excesses: I worked instead, partly through diligence but mostly because it was a cheaper way of getting through Saturday and Sunday. The labs and the library were forbidden to me on Monday afternoons, and my rotten little one-room apartment was almost impossible to study in because of the din of the fish market underneath it, the lack of a chair, and the thunder of Mrs. Bellis's bloody television soap operas booming through the thin wall from her equally small and squalid apartment next door. It was a depressing place to be at the best of times, but most of all during the day. The Rupolo charged seventy-five cents for admission on a Monday afternoon, which was just about within my budget. Besides, I told myself repeatedly in a desperate attempt to assuage my youthful guilt, it was important that I give myself at least some leisure time during the week, and Monday afternoon was as good a time as any to take it.

So, with my seventy-five cents in hand – a dollar if it had been an economical week, so I could buy some stale popcorn as well as my ticket – each Monday at two o'clock I would be outside the Rupolo, waiting for the doors to open. Inside, once I'd paid my money and crossed the musty-smelling foyer in the company of perhaps a couple of dozen other stalwarts, the routine for the afternoon was always the same: a feature, followed by trailers for forthcoming attractions, followed by another feature. Well before six o'clock, when the current main attraction would be shown for the first of its two evening performances, we would be out of there. The owner didn't bother to show any ads during these Monday-afternoon nostalgia fests: with an audience so small, and usually with several of them either sleeping or necking, it was hardly worth it – and nor was it worth his while to lay on any more staff than the minimum for these performances: there was just the projectionist – I assume, because I never saw one – and the old guy at the door who took the money for the tickets and, if required to do so, reluctantly moved over to the counter to sell vintage popcorn, dubious nuts and even more dubious candies. I never learned this guy's name either: he was just a hooked nose and a pair of bright little intense eyes and a hunched-over back. He never said anything more than "seventy-five cents" or "twenty-five cents" or, just occasionally, "fuck you."

The first time I went there it was a bright sunny September afternoon, and my guilt was thereby intensified. I could hear my mother's voice telling me I should be doing something outside, taking advantage of the sun and the fresh air. I might have turned and left, might have gone off to bore myself rigid doing something healthy and outdoorsy, were it not for the fact that the guy behind the cashier window took advantage of my indecision to reach through the gap and deftly extract my coins from the fingers that had been clutching them, replacing them with a dog-eared cardboard stub before I'd quite realized what was going on.

It was a pretty amazing double bill, that first one I saw. First up was The Wooden Horse; then, after trailers for Traitors Within and The Wind from the South, came The Dam Busters. In the first of these movies a group of British prisoners-of-war incarcerated in a prison camp in Germany used all sorts of stratagems to tunnel their way to freedom. The movie's title came from their use of a gymnastic vaulting horse to cover up some of their clandestine activities. Surprisingly, at the end of the movie, most of the prisoners did indeed succeed in achieving their freedom. I watched the trailers with that curious fascination one has when seeing extracts from movies one knows one will never actually trouble to see in their entirety, and then came The Dam Busters. This concerned itself with the efforts of an inventor called Barnes Wallace – I believe that was his name – to devise a sort of super-bomb that could skip across water and thus more effectively destroy Axis dams. Through much of the movie the other characters kept telling him and each other that the scheme was crack-brained, and I tended to agree with them; but in the denouement we saw that this seemingly implausible technique did in fact work. It was a part of the war I hadn't known about before – assuming it was indeed based on history rather than being just a screenwriter's fantasy – so I found the movie extremely interesting, even if Wallace's device didn't in the end alter the course of anything very much.

I was disappointed when the movie had to come to an end, as all movies do, and I emerged blinking into what was still bright sunshine. I picked up a hot dog from a corner deli and walked back to my apartment and Mrs. Bellis's television set with my inner eyes full of flickering black-and-white images, dark clouds and darker aircraft. Even as I strolled along the sidewalk, munching my hot dog – the frank had been overboiled, as usual – I was fully cognizant of the fact that I had been hooked. Whatever my mother's remembered voice might say on other Mondays, there was no way short of a broken neck I was going to miss another of these World War II double bills.

~

That night I phoned home – collect, of course – just to see how the folks were getting along and perhaps, if the conversation went along the right lines, to hint subtly that a cash donation would be joyously received.

"Hi, Mom. How's it going?"

"Very much the same. Your father's still got his indigestion. Have you met a nice girl yet there at the university?"

"Not quite, Mom. There aren't many girl students, you know." This was true, but it was an evasive answer to her question. I couldn't afford a girlfriend, and anyway, a late developer, still hadn't gotten over my adolescent neuroses about getting too close to any member of the opposite sex. My love life was confined to fervent and anatomically inaccurate imaginings about the body of one of the girls at the checkout counter in the local supermarket, to which mental images I would industriously manipulate a penis that I was convinced was too small. "I'd hoped Dad would be better by now."

"Well, it's all the stress, poor man."

My father had been retired for eight years, during which he'd done nothing more stressful than mow the lawn and complain about his indigestion. My mother, fifteen years his junior, put up with his self-pity rather better than I'd ever been able to, and was constantly ready with an excuse for his perennial and probably imagined ailment. This week it was stress. Next week it would be food additives.

"Glenda Doberman still often talks about you, Kurt. She's such a nice girl, don't you think?"

People often talk about dogs and their owners resembling each other, but Glenda Doberman was the only person I'd ever met who had come to resemble the dog after which her family had been named. The whole of the rest of her face seemed to have been designed as a pedestal for the prognathous thrust of her jaws and nostrils. And the similarity didn't stop there. I'd once been forced into taking her to a prom, and dancing with her had proved to be like dancing with a sackful of conger eels, all solid and unpredictable muscles. The obligatory necking session in the car afterwards, outside her home, had been a nightmare I preferred to forget. I had nursed a sprained shoulder for weeks afterwards.

"And I'm sure she'll soon meet someone ... worthy of her," I said, in what I hoped was a smooth deflection of the subject. Mom didn't know – and I certainly wasn't about to tell her – that soon after her eighteenth birthday Glenda had become known as Hershey Bar Doberman because that was reckoned to be the maximum a boy had to invest to get inside her pants.

"So like you, Kurt. Always wishing the best for other people." My Mom had illusions about my father, and they extended to me as well. Who was I to destroy those rosy

visions of hers?

"But you should be looking out for someone nice for yourself," she said. For her, people were either "nice" or they didn't qualify for an adjective. "You're going to be twenty-five next month ..."

"Mom. Dad was forty-one when he found you."

"Yes, but that was different."

There was no way I could argue with this.

"What's the weather like at home?"

"Oh," she said, "just weather. It's been hot for September."

"Same here."

There was a pause during which all we heard was an electrical rendition of someone's burger catching fire on the barbecue.

"Are you feeding yourself properly?"

"As well as I can, Mom. Money's a little bit tigh—"

"Make sure you eat plenty of vegetables."

"Well, vegetables are pretty expens—"

"And fruit. There are some nice apples in the supermarkets at the moment."

My hot dog lurched inside me. Under the watchful eye of the deli's owner, Mr. Perkins, I'd piled it as high with sauerkraut as I dared, on the basis that on a budget like mine one should grab free additional nutrition wherever one could. That had possibly been, in retrospect, a mistake.

"How are your studies going?"

"Very well indeed," I replied, relaxing for the first time during this ritual weekly inquisition. It was true. So long as I kept my nose to the grindstone for the rest of the academic year, my doctorate was in the bag.

"Well, do keep yourself safe, dear. Your father and I miss you very much indeed."

Dad missed me so much that he could never bring himself to come to the phone to talk to his only son. As I put the phone down, after the usual tepid goodbyes exchanged with Mom, I entertained the fantasy that finally, fed up with his constant grousing, she'd slaughtered him with his own lawnmower and buried the shreds in the back yard. I'd never have known if she had, for all the contact there was between him and me except during those vacations that I went home. Yes, at Christmas-time I'd arrive back at the family bourn to discover my mother waiting to make a tearful confession to me ...

Littlenose Collection The Magician

Littlenose Collection The Magician Qinmeartha and the Girl-Child LoChi

Qinmeartha and the Girl-Child LoChi Take No Prisoners

Take No Prisoners Warm Words & Otherwise: A Blizzard of Book Reviews

Warm Words & Otherwise: A Blizzard of Book Reviews Strider's Galaxy

Strider's Galaxy The Life Business

The Life Business